SDR data is from a survey of US doctorate recipients and therefore does not reflect the full scope of Ph.D.s employed in the United States. In addition, as it only surveys those who received their Ph.D. in the United States, it does not capture individuals who obtained their doctorates outside the country and then came to the US for additional training (ie, postdocs) and employment. Finally, as with all surveys, there is certainly some selection bias regarding who completes the SDR. Discussions and insights here are based on SDR data and will be limited in their generalizability based on inherent limitations in the SDR.

For more on the SDR methodology, see the Survey Overview details on their website.

Top 10 states for employing computer science Ph.D.s: DC, Washington, Massachusetts, California, Maryland, New York, Utah, Virginia, Oregon, New Jersey

Top 10 states for employing physical science Ph.D.s: DC, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Mexico, Colorado, Oregon, Connecticut, California, New Jersey

And many of these states are also top employers of engineering Ph.D.s.

Given these data you may have more luck pursuing Ph.D.-level employment in certain areas of the country over others.

Given a postdoctoral position is by definition temporary, one would expect the percent of all employed SEH Ph.D.s in a postdoc would be rather low. While the general proportion of Ph.D.s employed in postdocs is relatively low, some of the trends in postdoctoral employment are concerning.

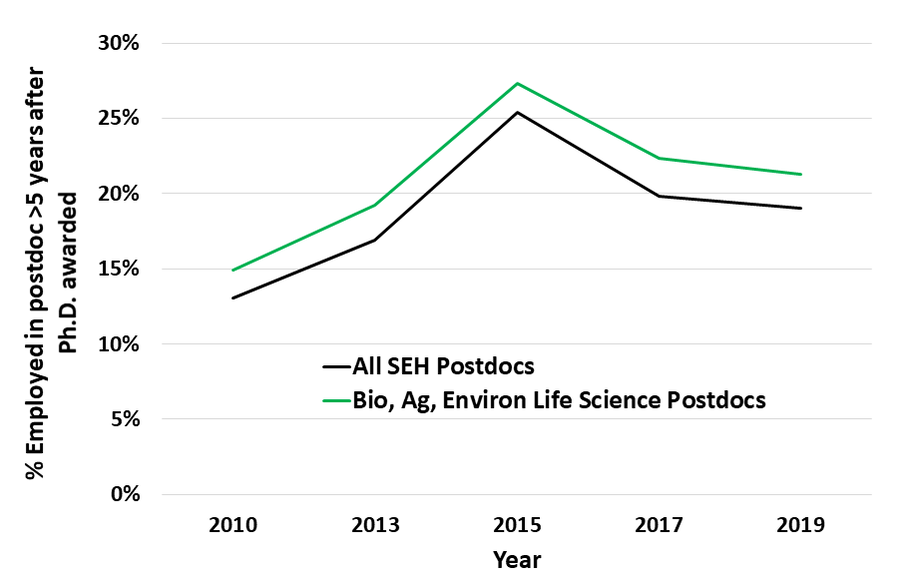

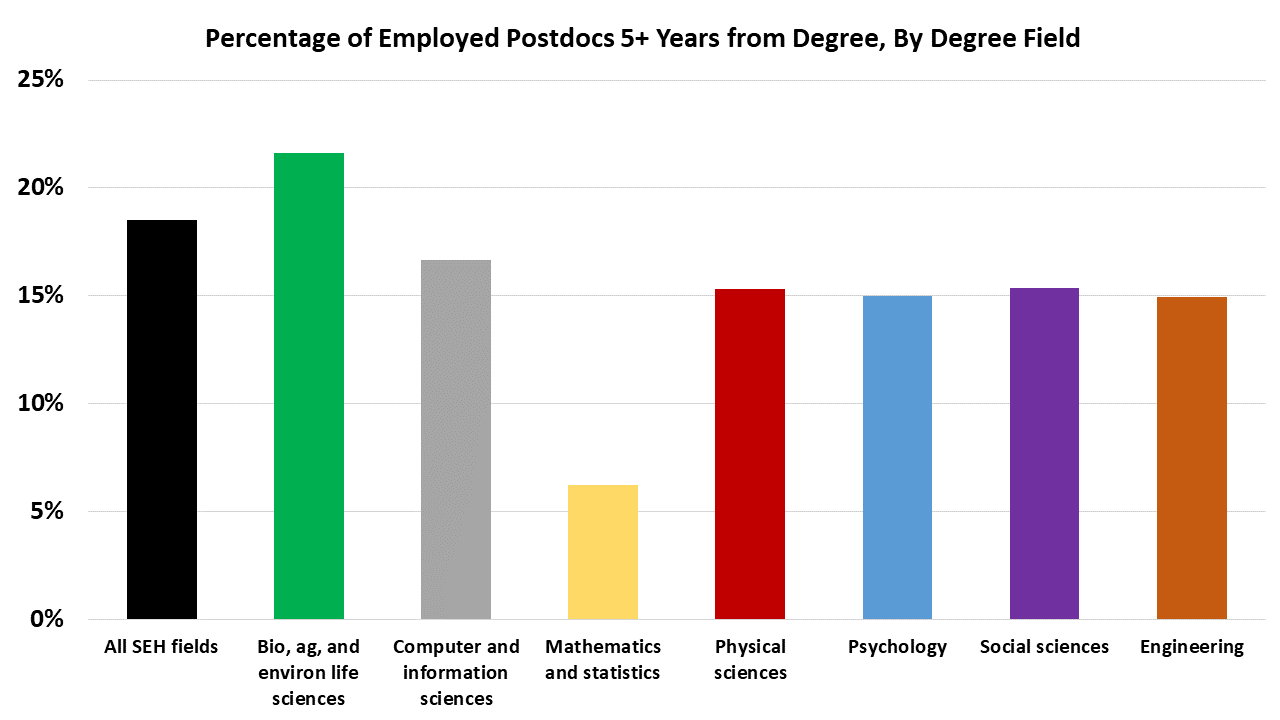

Unfortunately, many postdocs have been in their positions longer than the 5 year post-Ph.D. guidance outlined by The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine's The Postdoctoral Experience Revisited report released in 2014 (see press release). According to the 2019 SDR data, 19% of all science postdocs were >5 years from the date of their Ph.D. being awarded and this percentage was slightly higher (21.3%) for biological, agricultural, and environmental life sciences postdocs. So, as many as 1 in 5 postdocs employed in the US are 5+ years past receiving their terminal degree.

In addition, over the past 10 years a larger proportion of the US postdoctoral population is being filled by those 5+ years post-Ph.D. In the 2010 SDR data, only 13.1% of all science postdocs and 14.9% of bio, ag, and environ life science postdocs were >5 years from their Ph.D. being awarded. And while the 2019 data is off the peak of >25% of postdocs >5 years from their Ph.D. seen in 2015, the proportion of Ph.D.s employed as postdocs >5 years from their terminal degree is still ~45% higher in 2019 than 2010.

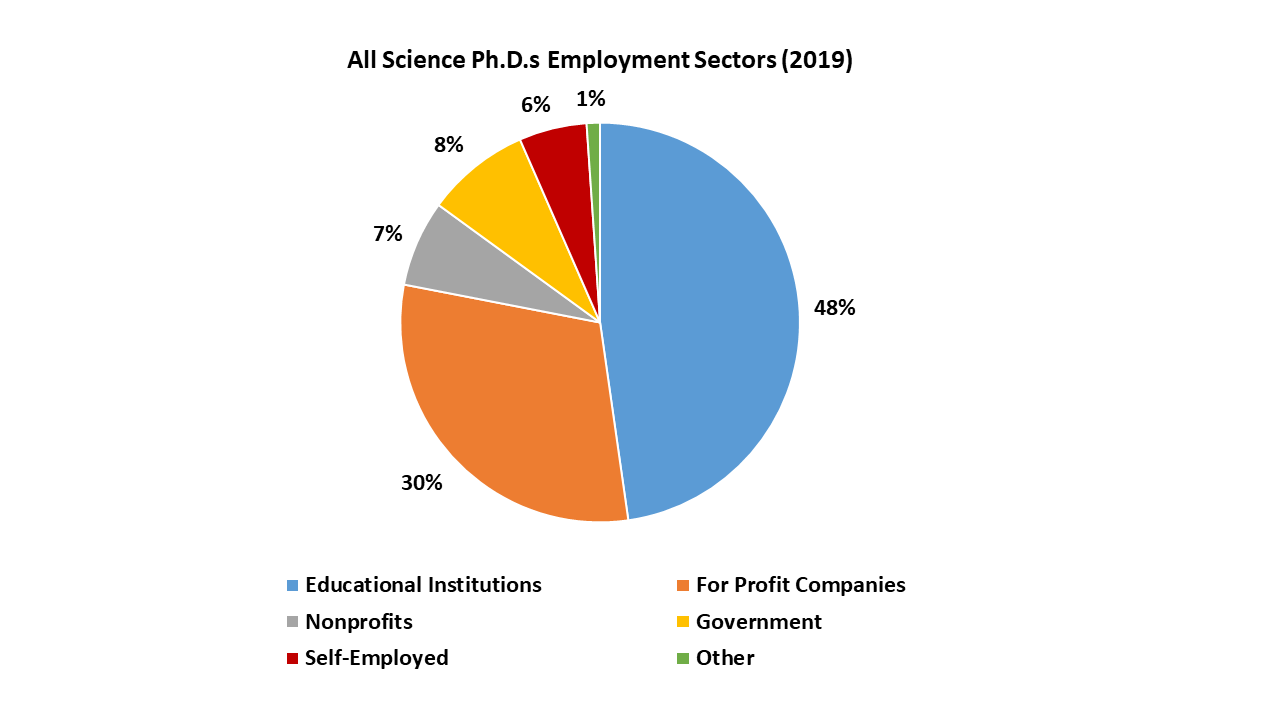

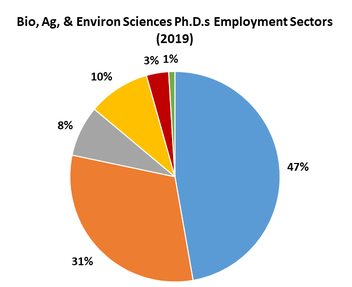

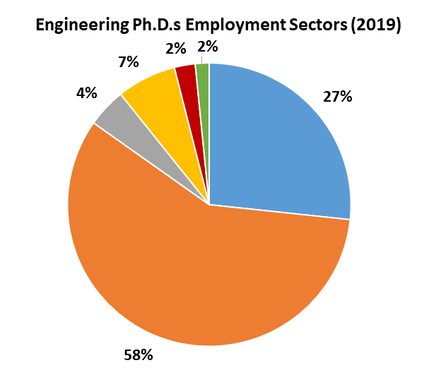

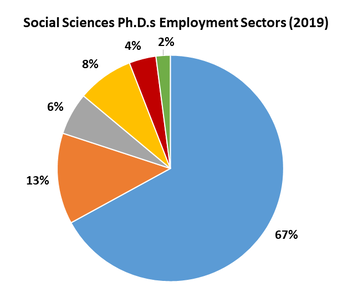

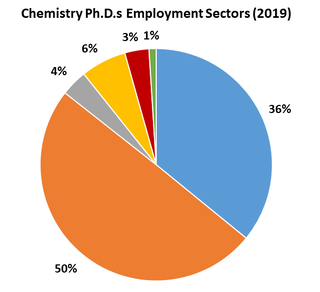

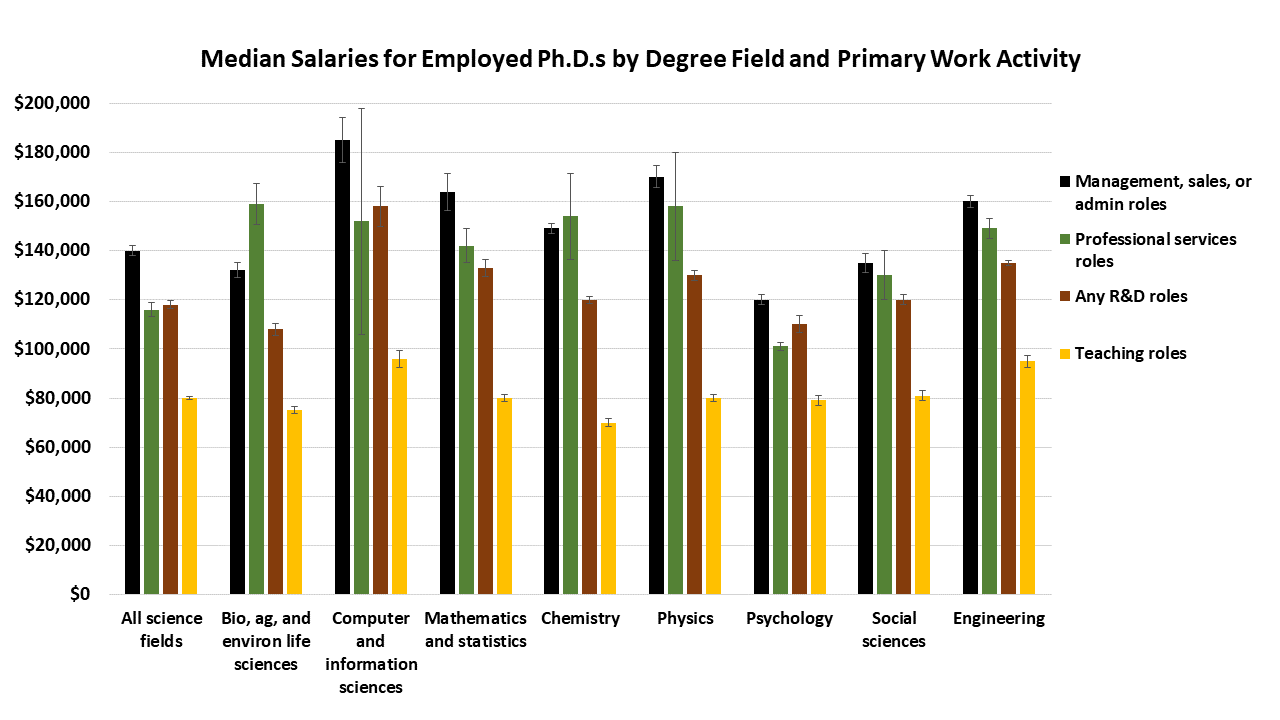

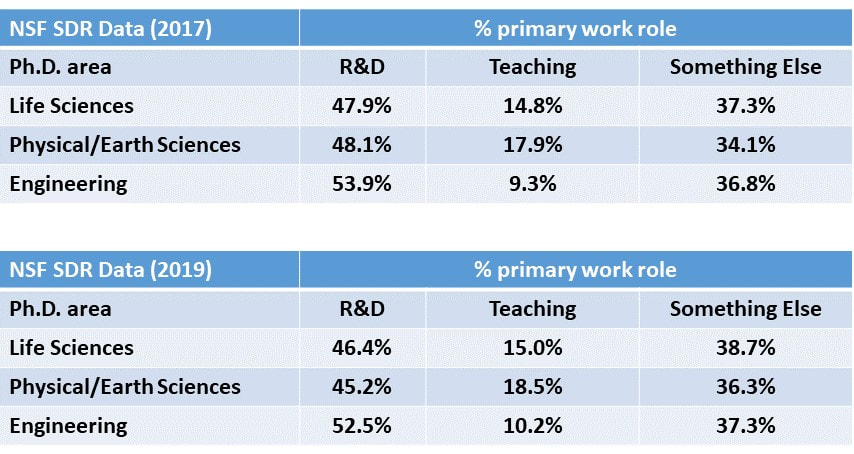

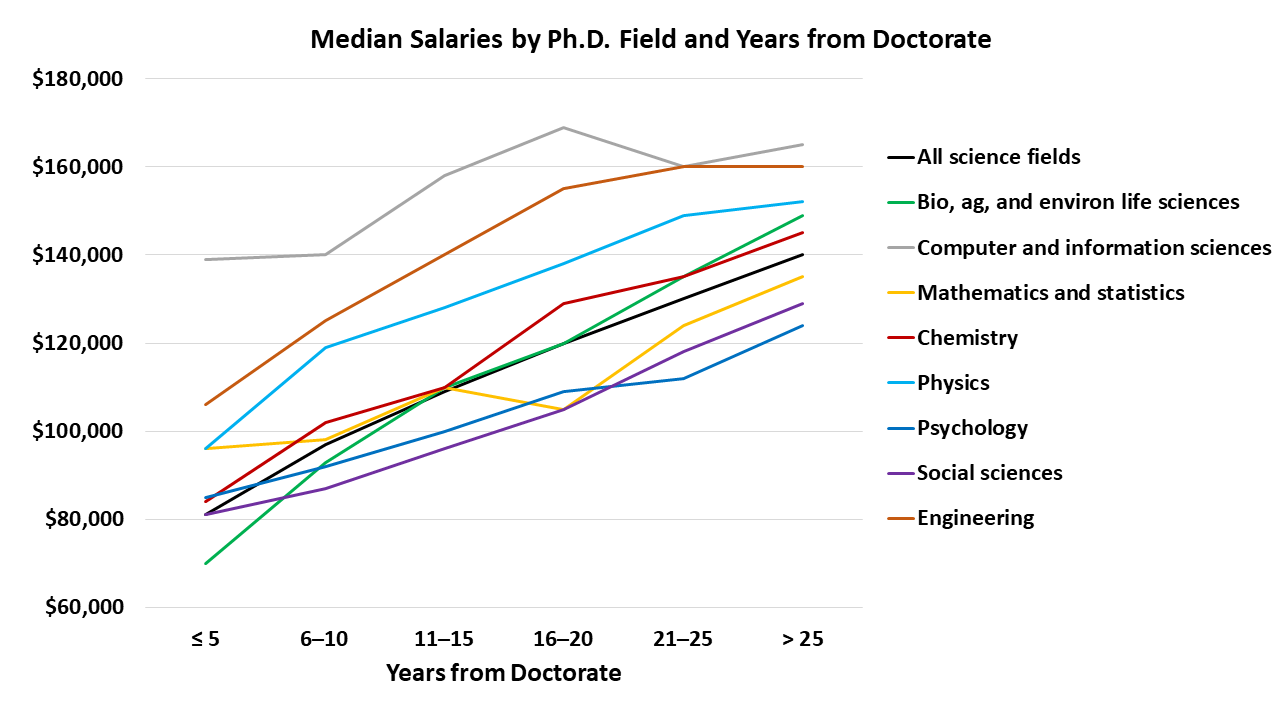

These data suggest certain sectors of employment may be more available to particular Ph.D. fields than others. It is difficult, however, to disentangle whether engineering and chemistry Ph.D. skills, for example, are more valued by for-profit companies than those in the social sciences or whether there is a greater openness to pursuing non-academic careers in these areas. It is possible there are things to learn from specific departments and programs who place Ph.D.s into diverse career areas that could be modeled by others. Certainly, providing diverse career pathways for Ph.D.s is critical as the "traditional" path of obtaining faculty positions becomes less available in many fields.

For instance, we know that many postdoctoral scholars in the United States are international, who either obtained their Ph.D. in the US and continued in postdoctoral training via various visa types or who received their Ph.D. outside the US before doing a postdoc in the US. The 2019 SDR shows that ~54% of US Ph.D.s employed as postdocs are US citizens and other data from NSF shows ~49% of postdocs in the US were born oversees. In some fields including computer science and engineering, NSF estimates 55-60% of Ph.D.s working in those areas in the United States are foreign-born. Thus, the various employment trends shared so far can be affected by various limitations to employment for those individuals requiring visa sponsorship by their employer, the frequency of which may differ by Ph.D. field and the proportion of international students and scholars working in that area in the United States. I discussed some of the challenges around being an international scholar in the US (including visa restrictions) in an earlier series of blog posts.

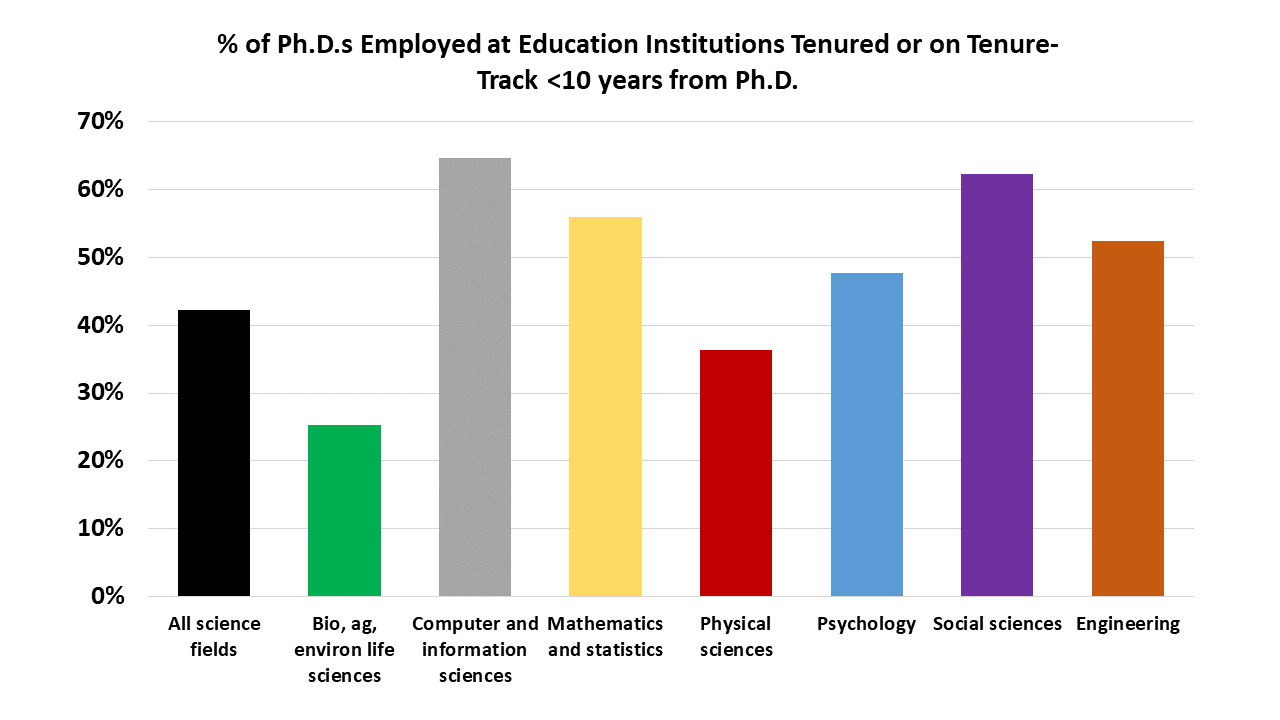

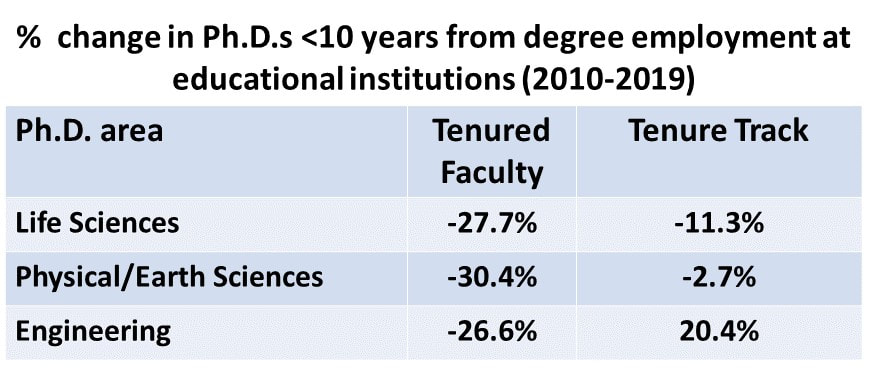

Regardless of how international scholar dynamics may affect these data, it is clear from the 2019 SDR data that there are vast differences in the proportion of "early career" Ph.D.s in tenure-track or tenured faculty positions based on their degree field.

The 2021 SDR data collection is currently underway and I will be very curious to see how these data look post-COVID. Will the percentages of early career Ph.D.s able to enter the faculty ranks fall even further? Only time will tell.

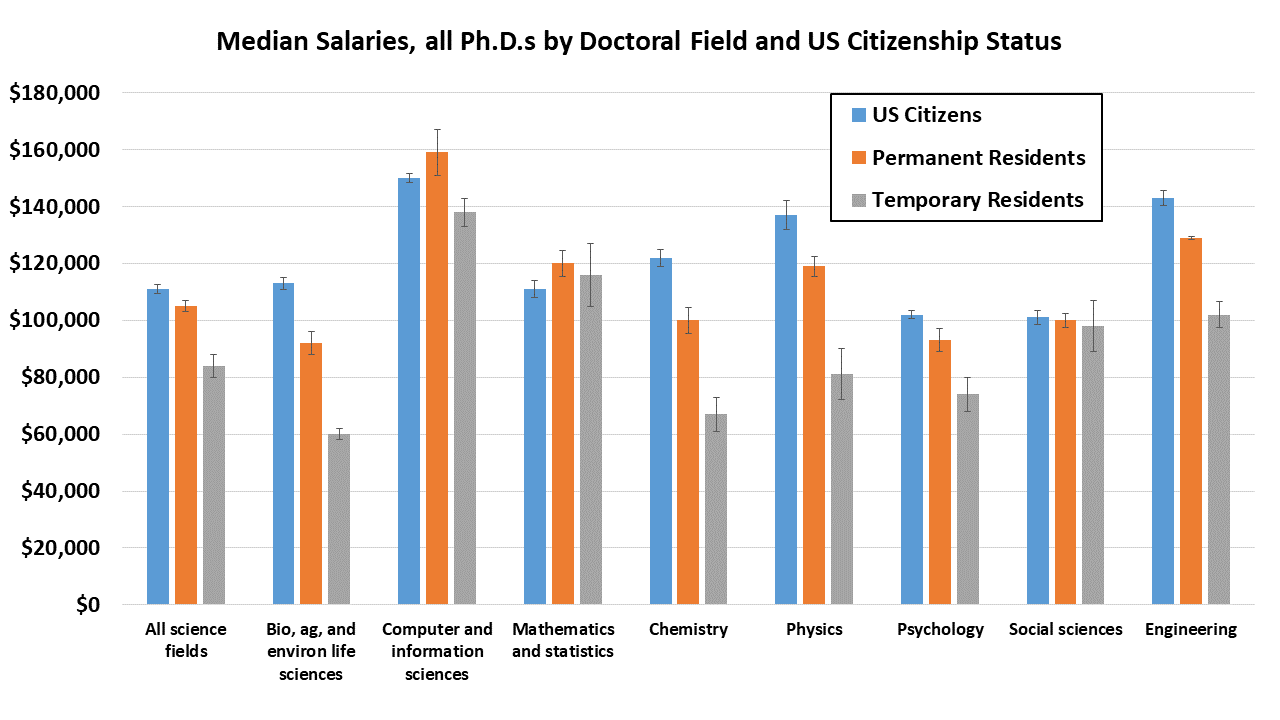

It is difficult to speculate too much on these data but one potential reason for lower median salaries for temporary visa holders in particular could be the result of many of these individuals working at US universities where the visiting scholar (J1) visa category is commonly used when an individual is working as a postdoctoral scholar or some other contingent, non-tenure track position (research associate). When a temporary visa holder is employed by a company, however, they require H-1B sponsorship which is subject to a "prevailing wage" which should prevent these individuals' salaries being below "market" rate, at least in theory. The largest sponsors of H-1Bs in the US are typically companies working in the computer & information sciences or data analytics where Ph.D.s in the areas of computer science, math, and statistics would be in high demand. So, the increased salaries for temporary visa holders in those fields could be driven by who is employing the doctorate recipients (technology companies paying high wages).

There are certainly glaring issues that are evident in the NSF data as well. The fact that many Ph.D. recipients <10 years from their degree employed at educational institutions are not in tenure-track faculty or tenured faculty roles speaks to the erosion of the faculty career path for many.

Furthermore, the proliferation of postdoctoral positions and other contingent roles is a problem. And while the number of those who received their Ph.D.s from US institutions officially employed in extended postdoctoral positions (5+ years post-Ph.D.) may be diminishing, we have less data on how many of these individuals have been captured by other job titles (such as research associate) when they "age-out" of the postdoc which may similarly lack pathways to permanent, well-compensated employment.

Certainly there are many unanswered questions in understanding the evolution of the Ph.D. workforce but NSF data provides critical insights which, when collected over time, allows for us to begin to observe changes in various employment metrics.

I encourage you to explore the data for yourself at the links below.

- PhD Recipients' Employment Trends: Insights from NSF Data

- The Challenges of Being an International Researcher: Implications for Advanced Degree Labor Markets PART 1 & PART 2

RSS Feed

RSS Feed