As this is a complex topic, I have divided it into two posts, to occur over the next two weeks.

First, we'll focus on international researchers in academia.

International Trainees in Uncertain Times

| And while I don't have the first-person perspective of an international researcher working in the US, I do interact with many of these individuals in my current work in postdoctoral affairs at NC State University where ~50% of our postdocs have countries of origin outside the US. I empathize with the unique challenges international students and postdocs encounter trying to work in the US while admitting I can never fully know what it is like being them. I am certainly not the first person to write about international graduate students and postdocs and the unique challenges they face. Here, though, I want to present my and other's perspectives on international temporary workers, including: |

- the value they bring to research and innovation efforts,

- the stress they put on labor markets, and

- how more transparency and data regarding their experiences and outcomes can help guide policies to support all advanced degree trainees.

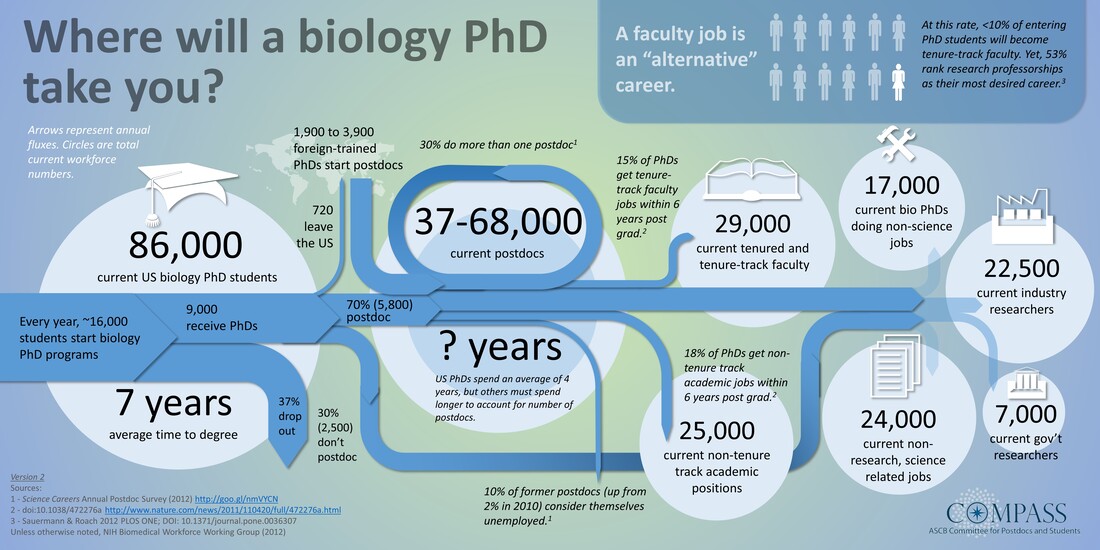

| International trainees have a large economic and productivity effect on the academic research labor force and higher education (including contributing tuition dollars) in the US, especially in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (the so-called "STEM" fields; see). Many have argued about the need to recruit these highly-trained researchers from other countries to the US. This thesis is based on the notion that the US has a deficit in STEM graduates and thus needs to import labor with that expertise, though whether such a deficit exists is not a straightforward state to measure and has been debated (see also). Indeed, some data indicate Ph.D.-holding US citizens employed in science and engineering has decreased over the period of 1973 to 1991 relative to non-citizens, which is at least partially explained by displacement of citizens with non-citizens within the advanced-degree STEM workforce. The US is a country of immigrants and it is an important component of American identity. Clearly, we as a country are stronger because of our diversity. |

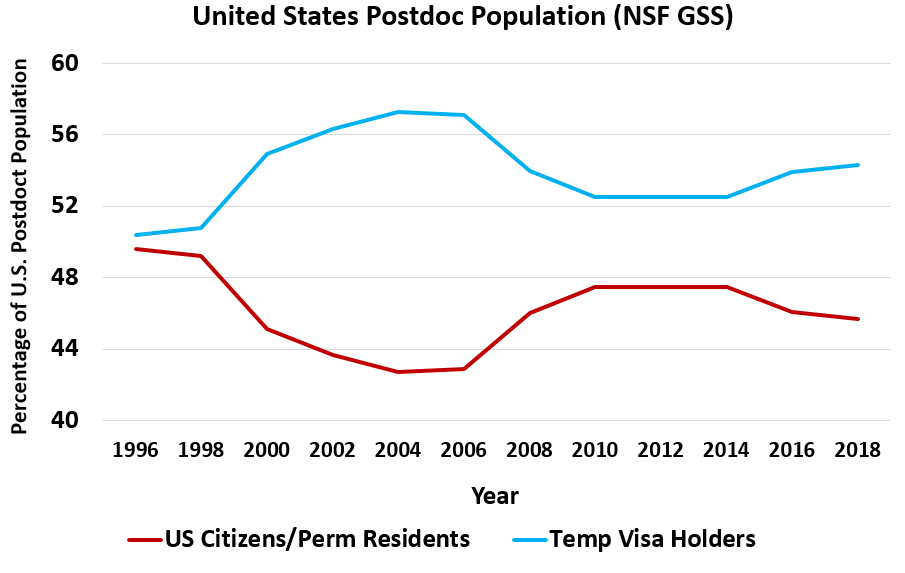

| 1/3 of Ph.D.s from US institutions are not citizens...17,500 people in 2018! Stay rates of Ph.D.s in US hover around 70% ~14% of the ENTIRE US scientific & engineering workforce with Ph.D.s are not US citizens >50% of US postdocs are temporary visa holders |

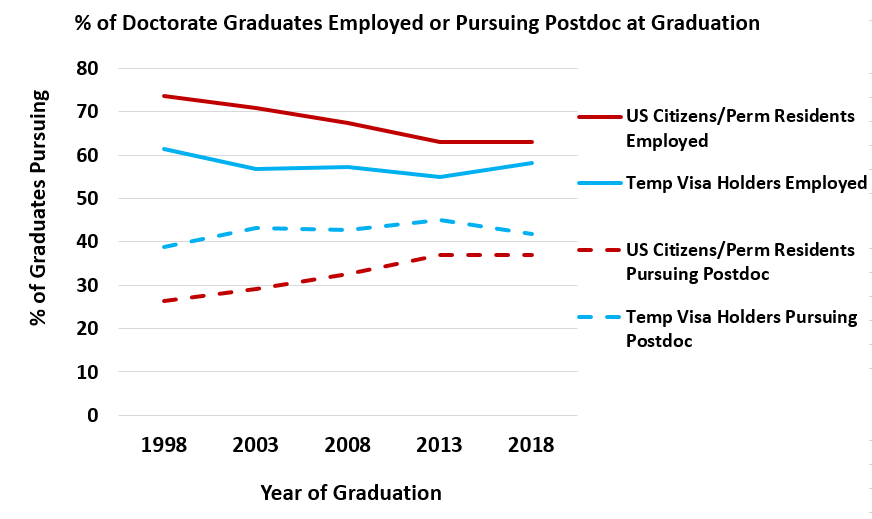

NSF's 2018 SED data reports ~72% of temporary visa holding Ph.D. recipients intend to stay in the US after they receive their degree. And this number has remained quite stable since 2012, averaging between 70% and 74%. Furthermore, 5 and 10-year stay rates from doctorate recipients in 2005 & 2010 range between 66% and 76% in science and engineering fields.

A working paper from George Borjas at the National Bureau of Economic Research has found that "a 10% increase in immigration-induced supply of doctorate recipients lowers the wage of competing workers by 3-4%, with about half of this adverse wage effect being attributed to the increased prevalence of low-pay postdoctoral positions." Indeed pursing a postdoc in general has been associated with lower initial and lifetime earnings though it is often an essential training step for those pursuing faculty positions and can be useful for one's career advancement.

By design, a postdoctoral position is both research and training and, as such, postdoc compensation has, historically, been low (see MD residents versus attending MDs as a somewhat comparable example). However, international postdocs often face even lower salaries. A Sigma Xi postdoc survey published in 2005 found temporary visa holding postdocs had a salary that was, on average, $2,000 lower than the median postdoc salary of $38,000. This data suggest international postdoc salaries could be ~5% lower than their peers.

| This salary discount is potentially the result of postdocs on temporary visas accepting lower "market" rates for their positions, which may potentially deflate postdoc pay across the system. Indeed, work by Xiaohuan Lan at the University of Virginia reports that a 1% increase in the share of temporary immigrants among new Ph.D.s decreases the relative wage of native postdocs to non-postdocs by 0.9-2%. As more temporary visa holders with Ph.D.s enter the system, they inflate the postdoc labor pool "supply" and decrease potential postdoc wages. |

Certainly required minimum postdoc salaries and initiatives that have prompted the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to consistently increase its NRSA postdoc stipend level (a common benchmark for postdoc salaries) are reducing salary inequities among postdocs. However, since these are suggested (for trainees not funded via NRSAs) or minimum (as determined by each university) salary levels, the degree to which compensation inequities exist between international and domestic postdocs remains largely unknown.

It is important to emphasize there exists a power dynamic in any academic research lab where the supervisor/principal investigator controls the fate of their trainees (by providing letters of recommendation, mentorship experiences, funding, etc...), which includes graduate students and postdocs. This dynamic can be even more imbalanced when the trainees are international and on either student or work visas. In fact, it crosses the line to exploitation more often than anyone in academia would like to admit.

| One may wonder why would a supervisor exploit young researchers trying to advance their careers? The fact that academic research is so pressure-filled doesn't help. Supervisors are normally faculty on the tenure-track trying to keep their own careers afloat. Some are still struggling to obtain tenure, others need that next grant to come through to pay a portion (or all of) their salaries or keep their lab open. It is not uncommon for postdocs, especially those on temporary visas, to report long work hours as they strive to support their lab's work. |

The plight of international researchers reflects a systematic problem: academic research and career advancement is under-supported.

Given their limited work options within the US, though, international postdocs who wish to stay have few employment options. This most often means taking research-related positions at academic institutions with titles such as research associate, research scholar, or research assistant professor. And whether these positions represent career advancement from a postdoc is questionable. Some see these roles as means to skirt the term limit rules for postdoc positions (typically around 5 to 6 years, see) while others see a path toward professionalization of researcher roles for former postdocs (see also). Further tracking of postdoc outcomes and career progression is needed to support these arguments.

What we do know from data collected in a 2016 national postdoctoral survey is that "residency status in the U.S." is a significant predictor of postdocs' career choices. Clearly, the career paths open to temporary resident postdocs are different from their permanent resident or US citizen peers.

| The H-1B work visa is a common path to employment for advanced degree holders seeking to remain in the US. H-1B sponsored employees, including postdocs, must be paid the "prevailing wage" for their work area, level of expertise, and geographic location of work. However, this determination of prevailing wage is open to much interpretation. In fact, some have argued and data have shown that H-1B employees at for-profit companies make lower salaries than their peers and that this mechanism is used to, potentially, suppress wages for all employees. |

So, the H-1B cap-exempt status of universities may contribute to the under-employment of international trainees, locking them into academic research support positions, especially given the low rates of these (and most Ph.D.-holding) individuals transitioning to more well-paid and stable tenure-track roles. Data from the US Department of Education show 3-3.5% of all tenure-track (Assistant Professors) and tenured professors (Associate or Full Professors) at US post-secondary institutions (universities and colleges) are not citizens or permanent residents. Looking just at the tenured professor population, the percent that are not US citizens/permanent residents is only ~1.4%. Obviously, there are various reasons for temporary researchers to not pursue a faculty position in the US from a desire to return to their home country to making the decision to not pursue a faculty route for employment in the US. However, for the international immigrant and temporary visa holding population to go from representing >50% of US postdocs to approximately 1.4% of tenured faculty and 6.5-7.0% of tenure-track faculty (definitely a better number in this younger population) at US institutions represents serious issues in career advancement that require further study and scrutiny.

Fifteen years after that report, while some studies, including those referenced in this piece, have been completed, MUCH remains unknown about the the international researcher population and whether it is a net positive or negative for the research enterprise. Some institutions have begun reporting outcomes data of their Ph.D. students & postdocs, which can in some cases be filtered by international status - see the Coalition for Next Generation Life Science initiative. But more outcomes tracking of the international trainee population in the US is needed, especially those who received their graduate degrees outside the country and pursued a postdoc in the US (as NSF's Survey of Doctorate Recipients and Survey of Earned Doctorates focus on US Ph.D. recipients only).

In my opinion, we are doing these individuals a disservice by allowing them to come to our institutions within the US to train and then not being able to easily support them in their career transitions when the data suggest a vast majority (70%+) wish to stay and work in the US. Expecting the number of individuals we train each year to be able to secure one of the ~85,000 H-1B visas sponsored by a for-profit company (more on this in next week's post) seems irresponsible. And if a company has to enter a lottery for the ability to even hire someone on an H-1B, we dis-incentivize them from using the mechanism effectively.

Thus, the pathway remains heavily tilted toward temporary visa holders remaining to work in academic settings, often in contingent labor positions, as postdocs, research associates, research scholars, research assistant professors, lecturers, etc... These positions often lack the ability for career advancement and pay wages that are below market value for these highly-trained researchers. The system allows these positions to exist, though. Academia is not immune to the pull of cheap labor.

In these uncertain times, being an international trainee is even more problematic. Traveling back to one's home country is not even feasible at the moment with the restrictions in place due to COVID-19. How we as institutions respond to the challenges of this vulnerable population will, I believe, be telling of how we deal with the coming issue of supporting the vast number of advanced-degree holders we produce each year.

International Student Precarity in the Humanities Academy

International Students and COVID-19

Choice of Country by the Foreign Born for PhD and Postdoctoral Study: a Sixteen-Country Perspective

Reports & Briefs on High Skill Immigration from the National Foundation for American Policy

The Future of the Postdoc

National Academies of Sciences. The Next Generation of Biomedical & Behavioral Sciences Researchers: Breaking Through Report

RSS Feed

RSS Feed