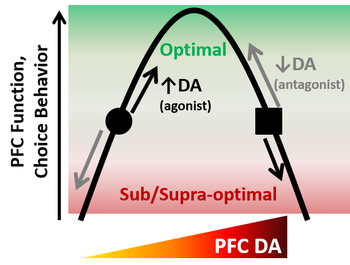

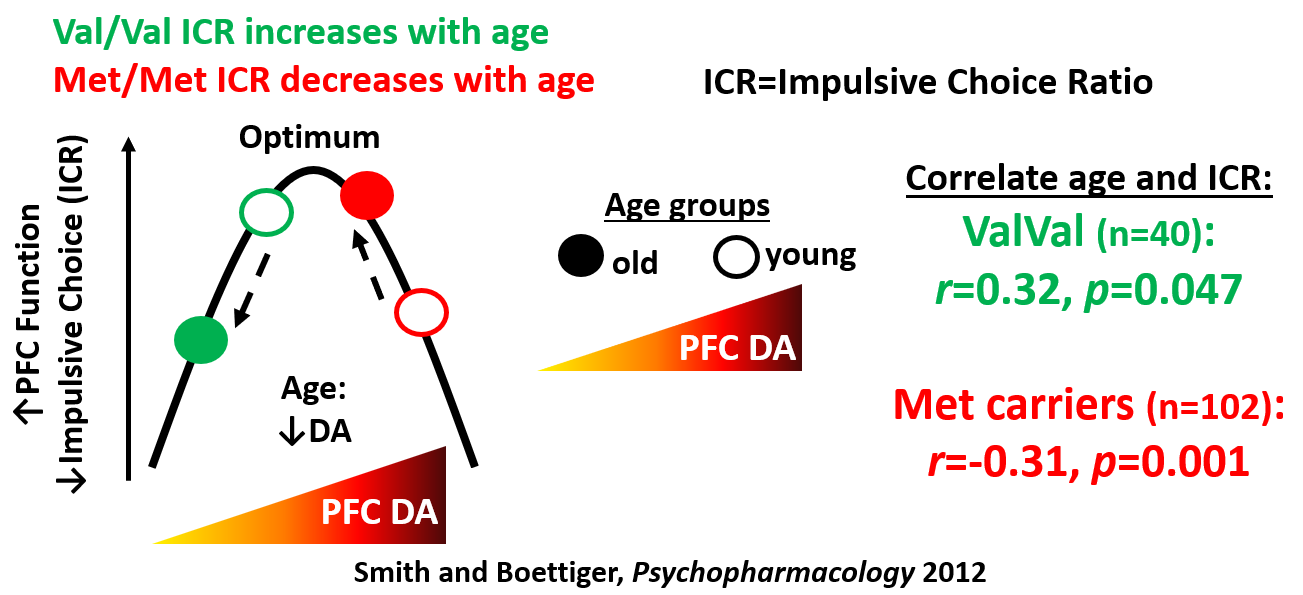

In fact, dopamine signaling in an area of the brain known as the prefrontal cortex (PFC) is critical for a variety of cognitive functions, including attention and processes such as working memory. Interestingly, dopamine's function on cognition has proposed to be non-linear (inverted U shaped) with some optimal intermediate level of dopamine associated with better cognitive performance. My own work in collaboration with Charlotte Boettiger and Amanda Elton has used the inverted-U model of PFC dopamine's effect on cognition to explain differences in working memory and choice behavior seen in healthy adults. We have also shown evidence of U-shaped patterns in resting and task-related brain function.

Dopaminergic signaling declines with age. A 2017 meta analysis led by Teresa Karrer has demonstrated declines in both the receptors that are the key target of dopamine signaling as well as the dopamine transporters important in the regulation of this signaling.

This decline has effects on a variety of decision making processes. It also has implications for the inverted-U model as natural declines of PFC dopamine with age would be expected to shift where individuals fall on the U-shaped curve.

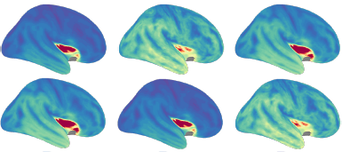

| My own work with collaborators David Zald, Greg Samanez-Larkin, Kendra Seaman, and Linh Dang has confirmed these persistent declines in dopamine signaling across the brain, with the rate of decline varying in different areas of the brain. Rates of decline vary from ~10% per decade in the frontal cortex to <5% per decade in the striatum, areas of the brain associated with decision making (also see) and reward, respectively. |

While our own data does not unequivocally support the correlative triad hypothesis of dopamine, aging, and cognition, this does not mean dopamine changes with age don't impact some aspects of human behavior. Work from the Samanez-Larking group and others has shown older adults are more likely to choose skewed gambles than younger adults, are less sensitive to monetary losses, and decrease their selection of risky monetary choices with age. See two excellent review articles on some of this aging & neuroeconomics literature here and here.

Our group, in work led by Kendra Seaman, has also found evidence that different types of commodities (social interaction and health) may be more valuable to older adults immediately and with certainty than money.

Interestingly, the brain regions responsible for assigning value to potential rewards are consistently engaged across adulthood. Thus, older and younger adults are using similar brain mechanisms to assign value to rewards. It is possible, though, that changes in dopamine signaling in these key reward valuation brain areas (ventromedial PFC, ventral striatum) influences to amount of value assigned to rewards as we age.

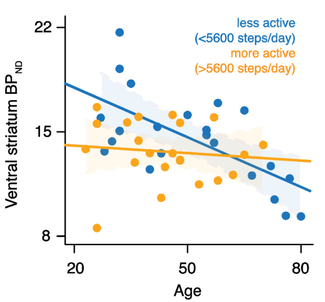

| Interestingly, our research group, in work led by Linh Dang, has found evidence that the negative relationship between age and dopamine receptor availability in a particular portion of the brain associated with motivation and reward processing (the ventral striatum, VS) was weaker in individuals with a higher degree of physical activity (as assessed using a pedometer). These data suggest that increased physical activity may slow age-related dopamine decline. The Parkinson's disease (a disorder associated with death of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain) literature is suggestive that physical activity can be beneficial. Whether exercise could work to slow or prevent dopamine decline in normal human aging remains to be empirically tested. |

An increasingly aging human population makes it critical to understand how decision making processes may differ between younger and older adults. Natural, age-related declines in dopamine probably play a role in reward and choice behavior differences between young and older adults. Understanding the differences between choice behavior with aging will allow more effective interventions to be developed to assist older adults in their financial and healthcare choices (see also).

More work is needed to determine if particular approaches (from pharmacology to exercise) can be taken to optimize PFC dopamine levels and/or prevent age-related declines in dopamine signaling.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed