Many bright and motivated graduate students and postdocs will be applying for these positions.

Landing a Faculty Job is Challenging

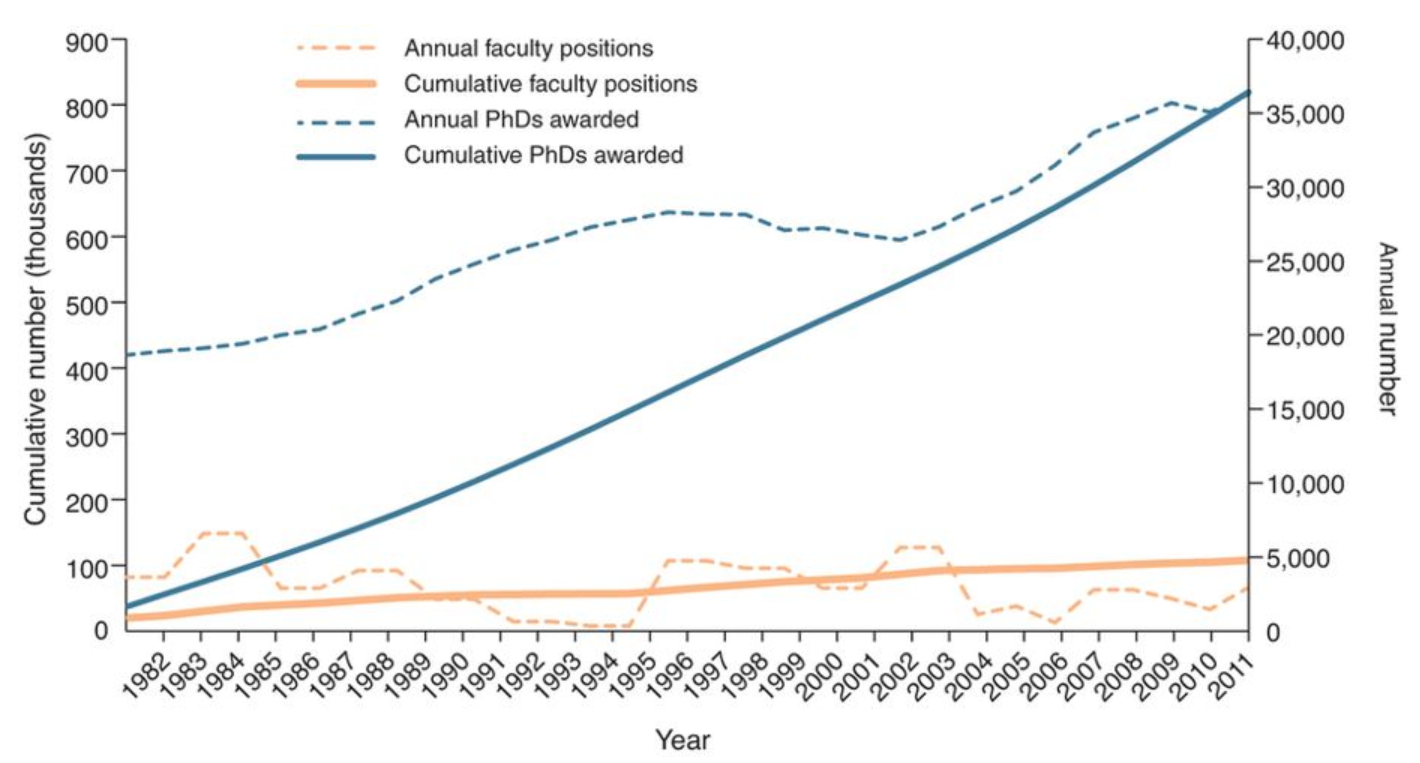

I think most know that it has become exceedingly difficult to land a tenure-track academic position (see a nice description of the process from one applicant here & see also). Data from the biomedical sciences estimate only ~20% of all Ph.D.s are working in tenured or tenure-track academic positions. In 2006, ~15% of US doctorates in biological sciences were in tenured/tenure-track positions within six years of completing their Ph.D.s with ~18% in untenured roles (postdocs, lecturers, research associates), this compared with ~55% in tenured/tenure-track roles in 1972.

Predictors of Academic Job Market Success

For some insight, see this nice piece on preparing for the job search. Quantitative studies have also begun to shed light on the hiring process. Perhaps not surprisingly, the number of first-author publications (particularly in high-impact journals) are strong predictors of who becomes a principal investigator, PI (i.e., faculty member running a research lab). In addition, making sure your research builds on but branches out from that of your graduate school and postdoctoral mentors is critical.

I am also working with a team from the Future_PI Slack group to better understand what metrics predict who receives academic job offers. We are still analyzing that data but what I can say is that the objective metrics of funding track record and high-impact publications are important but the effects are rather small. What that means is that what separates those who get job offers from those who don't is not such much the volume or quality of their work or their ability to attract funding. Rather, I believe, it often comes down to the more subjective measure of "fit."

UPDATED 7/28/20: See our eLife paper, A Survey-based Analysis of the Academic Job Market

UPDATED 6/29/22: Learn more about our faculty job market collaboration work and complete our faculty job market surveys for the 2020-2021 and/or 2021-2022 application cycles.

| What do search committees want? There are many pieces (see here and here and here) out there documenting the faculty search process from the point of view of the search committees themselves. FYI, these committees are composed of human beings making decisions and sometimes a hiring decision is about more than you as a candidate (i.e., politics and internal departmental power structures can come into play). What is "fit"? The illusive quality of "fit" is difficult to quantify and verbalize. How do you know if you are a good fit for a position and/or employer? It all starts with reaching out and speaking with people at the place(s) you want to work. |

1) Leverage your network to find out what search committees really want (i.e., are prioritizing).

2) If you are in doubt regarding your fit for a position, reach out to the search committee chair.

2) And thoroughly research the department to see if YOU think you would be a good fit.

It is important to learn more about what search committees want as a job advertisement often doesn't tell the whole story. Sometimes, committees don't even know what they want.

I will give you an example: I was forwarded a job advertisement for a genetic epidemiologist faculty position at a large, research-intensive institution a couple of years ago. I don't consider myself to be an epidemiologist. Though, I did some behavioral genetics research. Nevertheless, the department where this position was located looked like a great fit: interdisciplinary, growing, filled with faculty interested in understanding complex problems such as drug addiction (which I myself was researching) at all levels. I figured it was worth inquiring with the search committee chair whether I would be a good fit. I emailed him, attached my CV, and asked if I should apply for the open position. He replied back that this was an interdisciplinary position and they were looking for researchers doing a variety of interesting work in relation to the study of drug addiction.

I applied and SURPRISE, this was the only position I applied to (out of 26) where I got an onsite interview that year.

LESSON: NEVER assume you aren't a potential fit for a position. Research the department to see if YOU think you could fit in there. If the answer is YES, I encourage you to apply and make the case in your cover letter. Also, reach out to the search committee chair for some guidance. Sometimes they will give you the blanket "we encourage all interested individuals to apply." If that is the case, doing your own homework to make a decision on whether to apply or not is critical.

| Also, if the search committee chair can't give you more clarity on your "fit" and/or there is no chair mentioned by name in the job advertisement, reach out to members of the department doing work you admire and see as potential future collaborators. Set up a phone/Skype call to ask them how they like working there, what resources are available to faculty, what the typical teaching load entails, etc... You may be surprised what you learn from that conversation. When I was interested in a position at another large, research-intensive university, I reached out to a faculty there doing work I found interesting to see if we could talk about the department. He graciously agreed. |

Do your research & connect with potential future colleagues

Hopefully these personal accounts show you the importance of not just blindly submitting your materials to as many open positions as possible. If you take the time to do your research and talk to faculty in the department, you can better prioritize where to apply and how to tailor your materials to make the best use of your precious time. Applying to faculty positions takes a lot of work and energy but putting in the extra effort to connect with the search committee chair or other departmental faculty is more than worth it.

| STOP, TAKE A STEP BACK, & REFLECT If all these stats, amount of work required, and the apparent unpredictability of the job market has you questioning whether you should apply for faculty positions, that is more than OK. I think it is good to reflect on what you really want out of this next stage in your life. Faculty jobs have their PROS and CONS (see here & here & here) and there are MANY TYPES of faculty jobs, not just being a PI of a research lab at a research-intensive institution. You could work at a liberal arts college, community college (see also), or regional university (see also) - all of which highly value teaching. These types of positions are less focused on securing grant funding and the expectation to publish your work often (priorities when working at a research-intensive university) and may better fit your skills and interests. |

And what if you get that faculty job offer? First congrats! Second, reflect and ask yourself: Do you see the institution and department as a good fit? Will you enjoy living in the area? You shouldn't take a position because it is your only offer. You want to make sure it seems like the right place for you. And if you accept the offer but wonder if you can succeed as a faculty member or are afraid of "failing" while on the tenure-track, read this superb piece for some encouragement and inspiration.

I was barreling down the road to a tenure-track position and got as far as an on-site interview and the dreaded waiting game to see if I was going to receive an offer. Looking back now, I am glad I didn't. It would have been hard to turn one down.

I couldn't help feeling during that time though, that being a faculty member at a research-intensive university might not be the best fit for me. Did I really want to have to constantly be thinking about and writing the next grant application? Always be drafting and revising that next publication? Did I want to have to develop a large research arc for my lab that was both practical but also innovative? I realized that I really didn't want to do all those things. They were what I had come to expect from myself over 10 years of graduate school and postdoctoral work but they weren't things I enjoyed doing.

During my time as a graduate student and postdoctoral fellow I also really enjoyed mentoring and helping others with their career plans. I got involved in the Vanderbilt Postdoctoral Association and now I work in Postdoctoral Affairs. It is a better career fit for me than the tenure-track. I am still in an academic environment but I get to spend my time mentoring and helping talented postdocs navigate their career search and support them in their professional development. The work-life balance is great and I have a lot of autonomy in my new role. I think it is the right place for me at this stage in my life.

I hope all those reading this piece find what that right fit is for you, too. And realize it may change over time and that is OK.

Happy hunting!

Further reading & resources:

Great resources are available on getting your faculty application materials in order:

The Academic Job Search (from University of California, Berkeley)

Academic Careers: Start Here (from the University of California, San Francisco)

You can also find examples of my own application docs on my Job Search Resources page.

Making the Right Moves: A Practical Guide to Scientific Management for Postdocs and New Faculty

resource from Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

See also my Inside Higher Ed Carpe Careers piece on The Importance of Informational Interviews in your faculty job search.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed