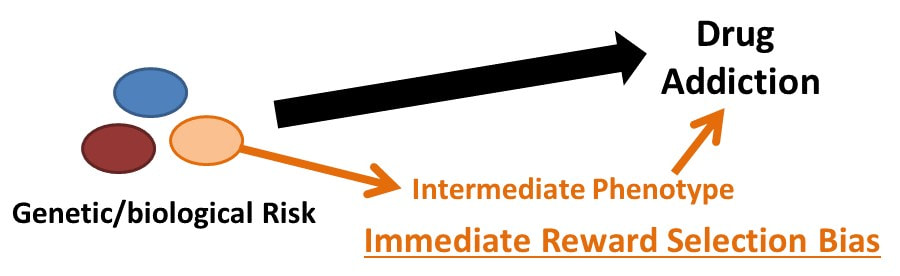

Given that substance use disorders (SUDs) are also complex disorders (people consume and continue to use drugs of abuse due to a variety of factors) with heritability estimates ranging from 40 to 60% (Heath et al., 2001; Verweij et al., 2010; Bierut, 2011; Agrawal et al., 2012), the identification of intermediate phenotypes associated with risk for these disorders is a growing focus of research (Karoly et al., 2013). Behavioral candidates for SUD intermediate phenotypes include reduced response inhibition (Acheson et al., 2011; Norman et al., 2011), increased risk taking behavior (Cservenka and Nagel, 2012; Schneider et al., 2012), aberrant reward responsivity (Wrase et al., 2007; Andrews et al., 2011), and increased discounting of delayed monetary rewards (Mitchell et al., 2005; Boettiger et al., 2007; Claus et al., 2011; MacKillop et al., 2011; MacKillop, 2013).

A variety of criteria have come to define an intermediate phenotype in psychiatry (Almasy and Blangero, 2001; Gottesman and Gould, 2003; Waldman, 2005; Meyer-Lindenberg and Weinberger, 2006):

- The phenotype should be sufficiently heritable with genetics explaining variance in the behavior.

- The phenotype should have good psychometric properties as it must be reliably measurable to be a useful diagnostic.

- The phenotype needs to be related to the disorder and its symptoms in the general population.

- The phenotype should be stable over time in that it can be measured consistently with repeated testing, potentially to assess treatment effects.

- The behavior should show increased expression in unaffected relatives of those with the disorder as highlighted by Egan et al. (2001), above.

- The phenotype should co-segregate with the disorder in families in that a family member with the disorder should show the behavior or trait to a greater degree than an unaffected sibling and that this unaffected sibling should display the trait to a greater degree than a distant unaffected relative.

- The phenotype should have common genetic influences with the disorder.

To illustrate the intermediate phenotype concept and associated criteria, we can look at research in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is associated with poor performance (and hyperactivity in an area of the brain known as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, dlPFC) on executive function tasks. As mentioned above, Egan et al. (2001) found unaffected siblings of those with schizophrenia to display executive function deficits that fell between unaffected nonrelatives and individuals with schizophrenia. Furthermore, genes affecting dlPFC activity and executive functions such as the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene explain variation in schizophrenia risk (see Egan et al., 2001). Thus, by investigating a specific behavior (executive function) and its neural correlate (dlPFC activity) in schizophrenic patients and those at increased genetic risk for the disorder, a genetic factor (COMT) was isolated. Schizophrenia is caused by more than one genetic variation but this example illustrates the value of identifying a link between a behavior associated with schizophrenia (an intermediate phenotype) and a potential biological and genetic basis for said behavior.

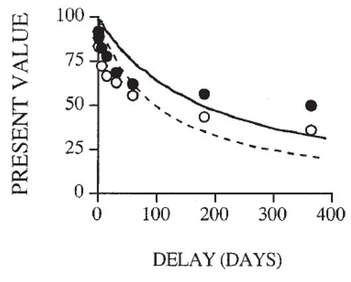

Conceptually, Now bias can be thought to have some relation to AUDs, as every relapse or excess drink represents a decision favoring immediate over delayed benefits. Furthermore, Now bias behavior has been shown to be heritable and associates with substance use, suggesting common genetic influences with SUDs (Anokhin et al., 2011). Importantly, Now bias as assessed through delay discounting (DD) tasks, has good psychometric properties (responses are highly reliable (Matusiewicz et al., 2013; Weafer et al., 2013)), suggesting it is a trait that is robust to consistent measurement (intermediate phenotype criterion 2). This is further supported by the fact that DD behavior is stable over time (Kirby, 2009). Thus, prior work has demonstrated Now bias satisfies many of the criteria for an intermediate phenotype for AUDs. However, not all criteria have yet to be examined.

In addition to being elevated in problematic drinking emerging adults, to satisfy another intermediate phenotype criterion for AUDs, Now bias behavior should also be elevated in unaffected first-degree relatives (parents, siblings) of those suffering from AUDs (intermediate phenotype criterion 5). Elevated Now bias in first-degree relatives of those with AUDs has yet to be adequately demonstrated, however.

Most of the intermediate phenotype literature considers the expression of the behavior or trait in first-degree relatives as critical in demonstrating that behavior as an intermediate phenotype. In the field of AUDs, however, positive family history of an AUD is often defined as having at least one parent with an AUD (Acheson et al., 2011) or father with an AUD (Crean et al., 2002; Petry et al., 2002), or some combination of parental history or sufficient density of AUD history in second-degree relatives (Herting et al., 2010). In these previous studies, the effects of family history on Now bias was either only observed in females (Petry et al., 2002), was not found at all (Crean et al., 2002; Herting et al., 2010), or was not present when controlling for group differences in IQ and antisocial behavior (Acheson et al., 2011).

Measuring Now bias behavior in individuals with any first-degree relatives with AUDs expands the classic family history positive AUD definition to include siblings, who display greater genetic concordance with a particular individual than their parents. To our knowledge, though, this definition of first-degree family member positive or negative for AUDs has not been applied to the study of Now bias. Thus, while Now bias possesses many properties that suggest it could be a good intermediate phenotype for AUDs, further investigation of this possibility is warranted, particularly work focusing on examining whether Now bias is elevated in unaffected individuals with first degree relatives with AUDs.

Given our review of the literature and past work in this area (Mitchell et al., 2005), we focused on better demonstrating the utility of Now bias as an intermediate phenotype for AUDs in a large group of individuals who ranged in age, level of alcohol use, and family history of AUDs. This work was published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience in 2015, but I share the key takeaways from the study, below.

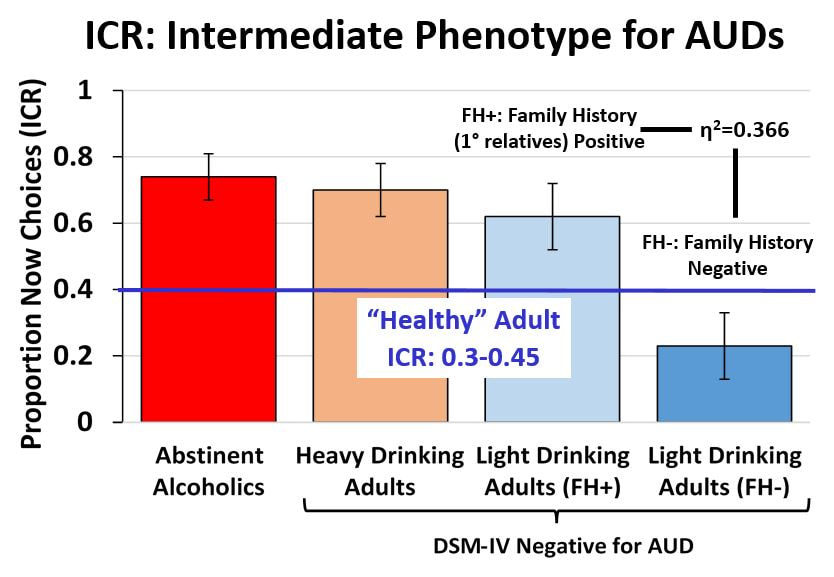

- Now bias (ICR) is high in individuals who drink heavily and problematically but without an AUD (orange bar in graph, below)

- Heavy drinker ICR is nearly equivalent to that seen in abstinent alcoholics (red bar in graph, below) despite these individuals not meeting the criteria of having an AUD

- Now bias is elevated in light/moderate drinking adults with first-degree relatives with an AUD (FH+) relative to those without a first-degree relative with an AUD (FH-; blue bars in graph, below)

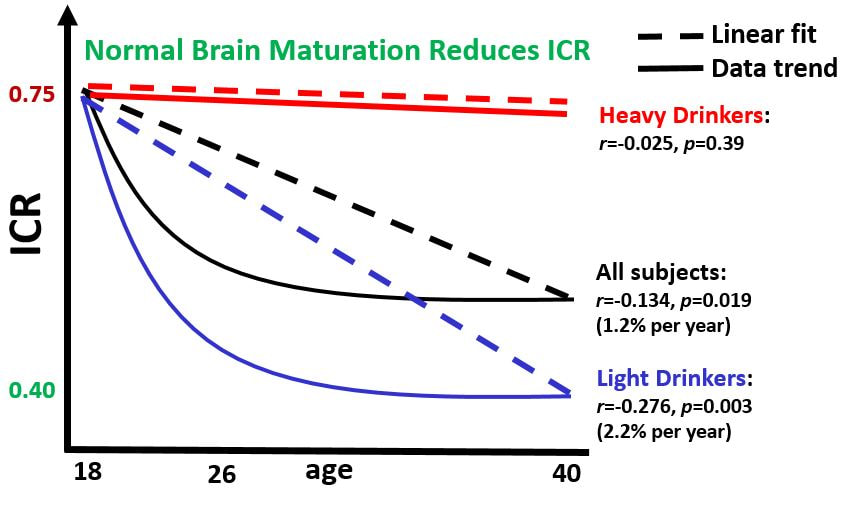

Ongoing work taking place as part of the Adolescent Brian Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study seeks to understand adolescent brain and cognitive development generally and the various behavioral (including Now bias) and neural risk factors that can emerge in adolescence that lead to mental or psychiatric disorders in adulthood.

Learn more about this ambitious study here and view current publications emerging from the dataset here.

- Large individual differences in intertemporal choice behavior (Review; Keidel et al., 2021)

- Genomic basis of delayed reward discounting (Gray et al., 2019)

- Steep Discounting of Future Rewards as an Impulsivity Phenotype: A Concise Review (Levitt et al., 2020)

- Individuals with two parents with addiction have significantly higher rates of discounting compared to those with no or only one parent with addiction (Athamneh et al., 2017)

- The density of familial alcoholism interacted with binge-drinking status to predict impulsive choice (Jones et al., 2017)

- A review of age & impulsive behavior in drug addiction (Argyriou et al., 2017)

- Age modulates the effect of COMT genotype on delay discounting behavior

- Ovarian cycle effects on immediate reward selection bias in humans: a role for estradiol

- Modulation of impulsivity and reward sensitivity in intertemporal choice by striatal and midbrain dopamine synthesis in healthy adults

- Neural Systems Underlying Individual Differences in Intertemporal Decision-making

And additional neuroscience topics on the blog:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed