UPDATE January 2021: I highly encourage readers to explore recent work in Science on Rethinking Immigration Policies for STEM Doctorates.

H-1B Visa Overview

The majority of advanced degree holders working in the United States (US) are sponsored under an H-1B visa for "specialty occupations". The program is administered through the United States Citizenship & Immigration Services (USCIS) and a job must meet one of the following criteria to qualify as a specialty occupation:

- Bachelor’s or higher degree or its equivalent is normally the minimum entry requirement for the position

- The degree requirement for the job is common to the industry or the job is so complex or unique that it can be performed only by an individual with a degree

- The employer normally requires a degree or its equivalent for the position

- The nature of the specific duties is so specialized and complex that the knowledge required to perform the duties is usually associated with the attainment of a bachelor’s or higher degree.

The success rate of "winning" the lottery hovers around 25% to 35%.

An employer who seeks to hire a foreign worker on an H-1B visa, then, must literally take a chance on them by entering a lottery to be assigned a visa for said employee. Even then, a company's paperwork might be filed improperly and the H-1B denied (a more common process in recent years as these visas have been scrutinized in more detail). All these steps require time and money to navigate, which dis-incentivizes companies from pursuing this path for a potential employee.

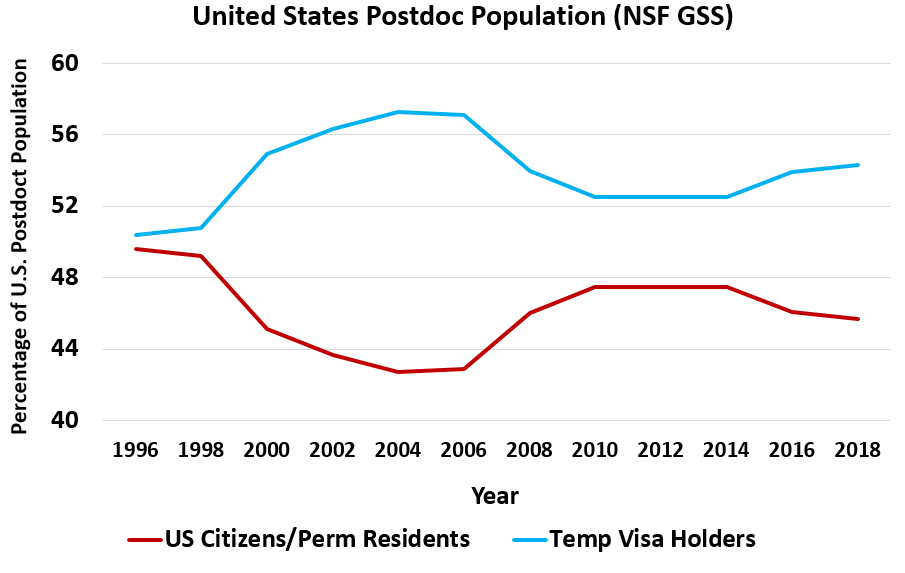

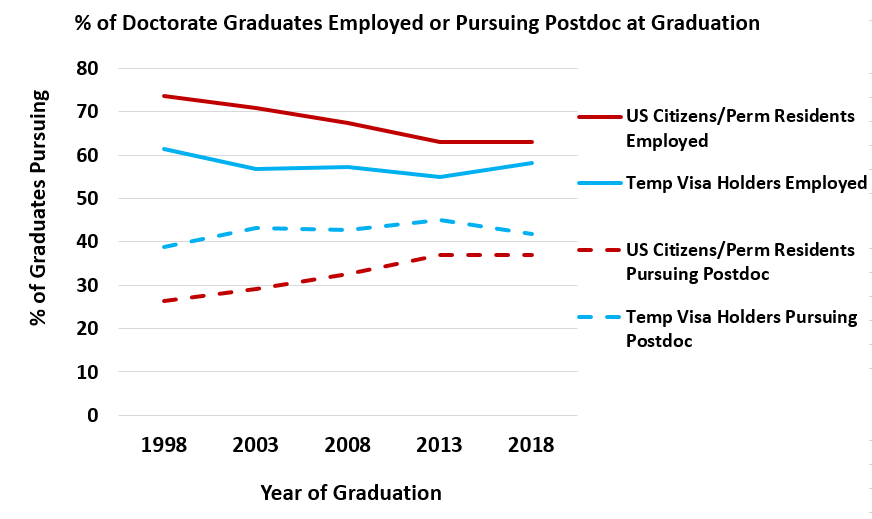

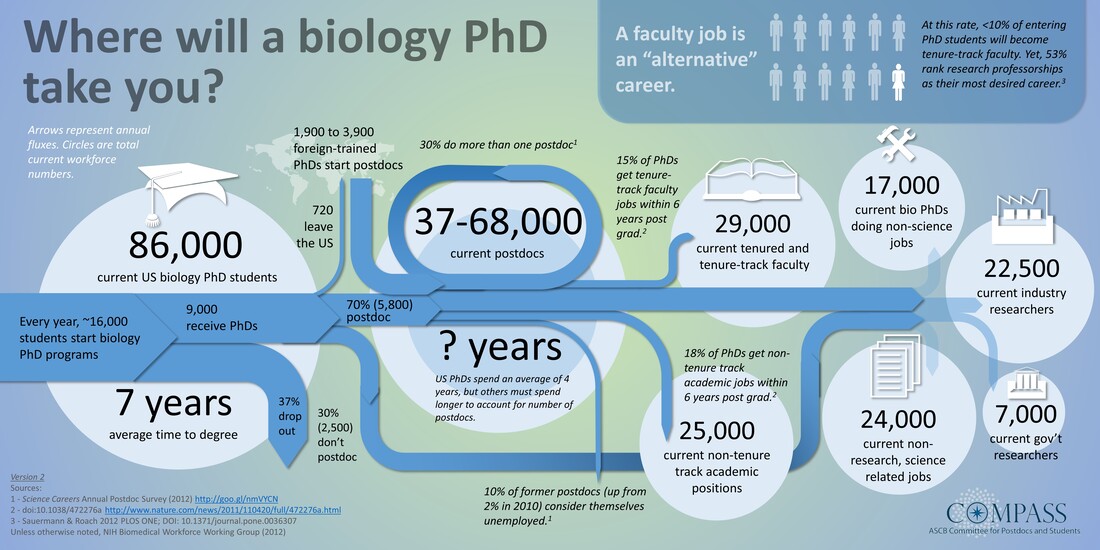

However, university and nonprofits are exempt from the H-1B cap (see last week's post for more on this), encouraging many nonimmigrant advanced degree holders to occupy positions in these institutions after completing their schooling.

Changes to H-1B Selection Process for Fiscal Year 2021

USCIS has taken some action to make the H-1B application process more efficient. This includes allowing employers to pre-register for a potential visa without the full paperwork being required until they have been notified whether they have been selected in the lottery. This change took effect for fiscal year 2021.

Another significant change for this fiscal year includes one that seeks to increase the odds for advanced degree (Master's or Ph.D.) holders being selected.

- The 65,000 general visa pool will be drawn first

- Followed by the 20,000 advanced degree pool draw

This order is the reverse of the previous process and USCIS estimates that it will result in an increase of up to 16% (or 5,340 workers) in the number of selected petitions for H-1B beneficiaries with a Master’s degree or higher from a US institution of higher education.

The main goal of the US's H-1B program is to fill gaps in the US workforce.

There is certainly debate around whether encouraging more advanced degree holders to enter the US has a positive impact on the economy. Some reports make a strong case for the value of advanced degree immigrants: showing they contribute more in taxes than they consume in benefits and their presence correlates with a higher number of American jobs. Others refute the interpretation of these data.

Indeed, there are many reports of how the H-1B visa program is being used to supplant American workers with visa holders, often with a cost savings to the employer.

H-1B Prevailing Wage and Fair Compensation

H-1B sponsored employees must be paid the "prevailing wage" for their work area, level of expertise, and geographic location of work. This presumably prevents a company from using the H-1B visa as a source of cheaper labor than hiring a US citizen. However, this determination of prevailing wage is open to much interpretation and abuse. In fact, some have argued and data have shown that H-1B employees at for-profit companies make lower salaries than their peers and that this mechanism is used to, potentially, suppress wages for all employees.

Furthermore, outsourcing Informational Technology (IT) consulting companies including Infosys, Tata Consultancy Services, Deloitte Consulting, and Cognizant are often used to circumvent some of the prevailing wage rules that apply to H-1B visas. And these consulting firms employ large numbers of H-1B visa holders (though mostly those holding a Bachelor's Degree). In the most recent 2019 H-1B data, the four aforementioned consulting firms employed 32,357 H-1Bs...the top four other for-profit employers (Amazon, Google, Microsoft, & Facebook) employed 22,202.

So, how much are H-1B holders being paid?

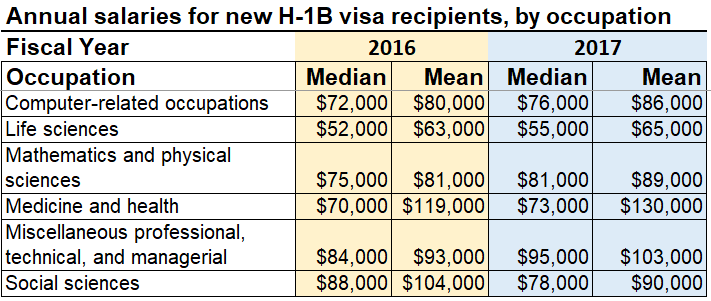

Data from NSF's Science & Engineering Indicators 2018 reports median income of H-1B visa holders for initial employment obtained from USCIS. Below are data taken from USCIS for fiscal years 2016 & 2017.

USCIS has extensive data on those receiving H-1Bs over the past several years on its website.

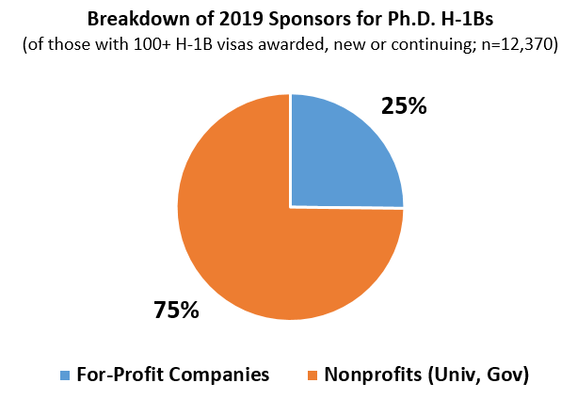

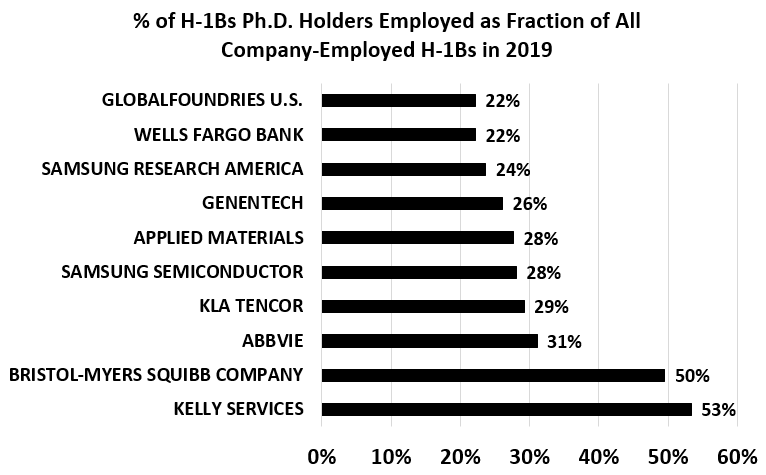

Below, I present some details from the "Approved H-1B Petitions by Employer" data from 2019. First, the cap-exempt nature of nonprofit institutions, which includes universities, academic medical centers, hospitals, and government institutes and labs, results in these employers representing a majority (75%) of Ph.D. H-1B employers in 2019 data.

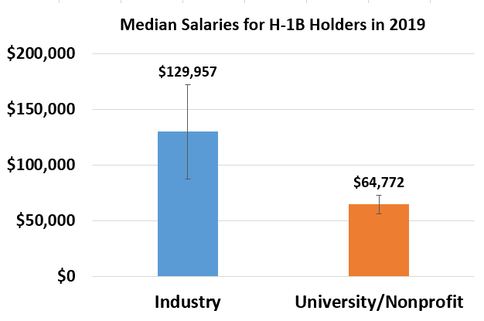

And as most H-1B holders in for-profit companies ("industry") are working in the computer science and engineering space (~60% of all H-1B holders, see report) where salaries are rather high, it is unsurprising that their industry salaries are well over $100,000 (where the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports mean annual earnings of ~$94,000 and ~$101,000 across all employees in the computer/mathematical and engineering sectors, respectively).

Interestingly, and supportive of the notion that job outsourcing companies may be used to suppress wages, the average median salary of H-1B holders employed by Cognizant, Tata Consultancy Services, Deloitte Consulting, and Infosys was $90,798 (+/- $14,340) versus $139,358 (+/- $8,407) employed at the four largest other for-profit employers (Amazon, Google, Microsoft, & Facebook). Note, this is not a perfect comparison as the 4 outsourcing/consulting companies rarely employ Ph.D.-holders.

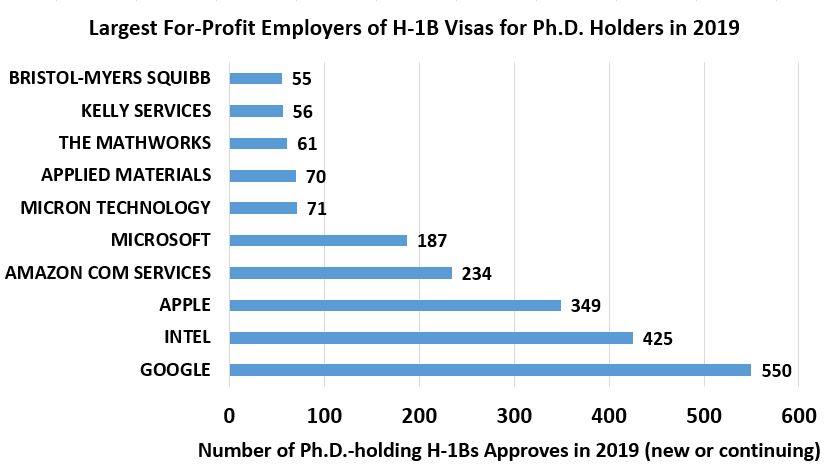

Relevant to my work supporting postdoctoral researchers, who all possess Ph.D.s, I wanted to better understand which for-profit companies employ Ph.D.s on H-1B visas.

The list is dominated by big-tech (see chart, below). In fact, Google, Intel, Apple, Amazon, and Microsoft employ ~56% of ALL H-1B holding Ph.D.s in for-profit companies (of those sponsoring at least 100 visas) in 2019.

Indeed, an earlier report looking at occupational groups by H-1B cap status in 2010-2011 found that computer science related occupations represented ~51% of all capped (for-profit) H-1B employees, followed by those occupying engineering roles (~9%) or working in financial services (~6%). This distribution differs when looking at H-1Bs awarded in the cap-exempt category utilized by universities and nonprofits: life scientists (~28%), postsecondary teacher (23%), health practitioners (14%), and physical scientists (7%) were the most common categories.

Clearly, roles that focus on computer science, technology, and engineering are disproportionately represented in for-profit H-1B sponsorships. So, if you are an international student or postdoc seeking employment with a company in the United States, you should work on developing your data science, coding, and other analytical skills that are in demand.

See these pieces and personal accounts of those who successfully transitioned to a career in data science.

Kelly Services, which contracts with the federal government to staff a variety of roles in government agencies, has the largest percentage of its H-1B workers occupied by those with Ph.D. degrees. Several pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbvie, Genentech) appear on this list as do some companies that might be less well known to the casual Ph.D. student or postdoc: KLA Tencor and Global Foundries.

What effect does utilizing H-1Bs have on their sponsoring employers and co-workers' earnings?

Much commentary has called into question whether the H-1B program is a net benefit or detriment to labor markets with some researchers describing a reduction in estimated wages and domestic employment in high tech sectors without the program.

Data looking at the effects of H-1B workers in for-profit companies suggest that payroll per employee may be slightly reduced for those companies who "win" the H-1B lottery. In addition, corporate profits are higher in those companies employing H-1Bs. Indeed, one report estimates usage of skilled H-1B holders placed in discounted prevailing wage levels, which the employer is allowed to select with little oversight or vetting, can save employers around $40,000 per employee per year (see details here). And stories of H-1B holders replacing US domestic workers in tech are plentiful.

|

A separate piece of research investigating the computer scientist labor market, estimated that in the absence of H-1B holders, wages for U.S. computer scientists would have been 2.6-5.1% higher in 2001 AND that employment in the field by U.S. workers would have been 6.1-10.8% higher.

|

Many temporary workers on H-1B visas wish to transition to permanent residency status in the US (i.e., obtain a green card). Many for-profit employers will sponsor green card applications for their H-1B employees. Those with advanced degrees can purse the EB-2 "exceptional ability" employment-based immigration path to permanent residency. However, country-specific caps make queuing for one of these immigrant visas a long process.

|

The current H-1B and immigration system in US is under intense scrutiny by the White House. Surely changes to these processes are needed and modification to the awarding of green cards have been proposed in Congress. But in its current form, this legislation may preferentially benefit Indian workers where the green card backlog is over a decade long. In addition a "points-based" system (RAISE Act) to prioritize immigration was introduced in Congress in 2017 but failed to receive necessary levels of support. Canada currently runs such a system and has seen growth in its educated immigrant population as a result.

|

Big tech and business interests are often involved in shaping the visa and immigration reform conversation via groups such as FWD.us. The large IT outsourcing firms that employ H-1Bs have also engaged in lobbying to prevent changes to the H-1B system. Certainly some of these business leaders, at least partially, mean well in their efforts. But to pretend there are not vested financial interests in ensuring a steady supply of often under-paid immigrant labor, who then depend on being "in good standing" with their employer for green card sponsorship, would be naive to any impartial observer. And the long backlog for green card processing for some groups, especially Indian workers, has also been suggested by some as another way companies may "lock in" their employment for many years. These workers have little career mobility and negotiating power as they wait on their employer-sponsored green cards to process...which can take over 10 years to occur, even for those in the exceptional ability EB-2 category.

With all this said, perhaps it is unsurprising that some have likened the current work visa system to modern-day slavery or indentured servitude (see also) as the workers' ability to remain in the US depends on their current employment with a set employer. This employer-employee power imbalance is highly problematic and may prevent visa workers from raising any employment concerns with authorities for fear of their sponsorship being revoked. Reforms clearly are needed.

Clearly, balancing the positive impact of temporary and immigrant workers on firm productivity and innovation with their potential negative effects on US labor markets and the well-being of the visa workers themselves is a difficult task. Diversity has been linked to greater creativity and innovation. However, the accounts referenced in this post suggest some for-profit entities utilize the H-1B and future citizen sponsorship to lock immigrant workers into roles that are underpaid with little room for advancement.

While the current political climate in the US has resulted in serious changes in how the H-1B visa system operates (for better or worse; see also), most would agree that the spirit of this system is a good one: encourage high-skilled workers to bring their talents (and associated spending and tax base) to the US.

Certainly some recent changes to how H-1B visas are reviewed and approved have been good. For example, there has been a decrease in the number of H-1Bs awarded to IT outsourcing consulting firms (traditionally, the bad actors in the system) and subsequent rise in those awarded to large tech companies in recent years.

The economic and demographic consequences of not doing so are many. This includes the important effects of immigration on US population growth and workforce participation, while saying nothing about their effects on technological innovations and discoveries in STEM.

Is America Still the Land of Opportunity?

America bills itself as the land of opportunity and many highly skilled and educated individuals from across the world come here to better their lives - to pursue the proverbial American Dream.

In addition, most (78%) Americans support high-skilled immigration to the country. However, we as a nation must do better to provide true opportunity to those who come to the US to study and work and ultimately wish to contribute their talents and abilities to the US workforce. We must also resist the influence of corporate interests and political operatives who seek to shape the work visa and immigration process to serve their own needs.

Our current processes negatively affects highly skilled and motivated individuals who have frequently trained for advanced degrees at US institutions. We as a nation have invested in these individuals and stand to gain financially for allowing them to live and work here. International trainees and workers have also made the often difficult choice of coming to this country to better their lives and, in the process, the lives of others including their current or future children and American citizens. The least we can do is create a system that helps them do so.

Only then can we fulfill our full potential as truly the land of opportunity to all.

The H-1B Visa Program: A Primer on the Program and Its Impact on Jobs, Wages, and the Economy

The H-1B Visa Issue Explained

The H-1B Visa Debate, Explained

U.S. Degree? Check. U.S. Work Visa? Still A Challenge

The Pandemic’s Effects on Recruiting International STEM Trainees

Are foreign students the ‘best and brightest’? Data and implications for immigration policy

Guestworkers in the high-skill U.S. labor market. An analysis of supply, employment, and wage trends

Is There Really a Shortage of Skilled Workers?

STEM crisis or STEM surplus? Yes and yes

The Skills Gap: Is it a Myth?

Paying Skilled Workers More Would Create More Skilled Workers

Upcoming H-1B lottery gives US-based advanced degree candidates an edge over foreign degree ones

RESOURCES

USCIS H-1B Employer Hub (search for companies who have sponsored H-1B visas)

Additional H-1B Data

US Department of Labor H-1B Willful Violator List

What is a willful violator?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed